Health

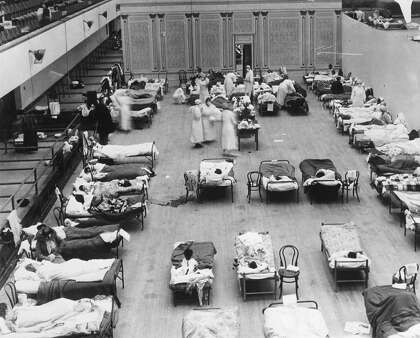

The first great San Francisco pandemic came to a close with a citywide celebration, at noon on Nov. 21, 1918.

A whistle blew, church bells rang and citizens who had endured sickness, death and many hard days of sacrifice to battle the Spanish influenza tore off their mandatory masks and threw them into the streets.

“After four weeks of muzzled misery, San Francisco unmasked at noon yesterday and ventured to draw its breath,” The Chronicle reported the next day, describing the scene. “Despite the published prayers of the Health Department for conservation of gauze, the sidewalks and runnels were strewn with the relics of a torturous month.”

Except that wasn’t the end. The flu roared back in January, nearly doubling the death toll, and taking advantage of a city that had completely let down its guard. The Bay Area, up until then a national pandemic success story, became a cautionary tale.

History is full of lessons, but this one seems to be screaming through the decades, more than a century later, carrying a message for this exact Bay Area moment. As some locals in 2020 strain to interpret positive coronavirus trends as an excuse to relax orders in the Bay Area, the dead of 1919 whisper: “Make sure you don’t give up the fight too soon.”

After the influenza arrived in San Francisco in late September 1918, the city was quick to take aggressive steps. Along with school and church closures, city leaders ordered the shutdown of theaters and a ban on public dancing. On Oct, 24, 1918, the Board of Supervisors ordered every citizen to wear a mask, with police fining and jailing those who refused.

Among the so-called “mask-slackers”: Mayor James “Sunny Jim” Rolph, who was photographed without a mask at a boxing event and charged a $50 fine.

The day after the 1918 mask order, the city hit its influenza peak, with 94 San Franciscans perishing in a single day. (As of April 8, 2020, officials report just 10 San Francisco deaths total caused by the coronavirus.)

By early November, the measures appeared to be working, with 10 new cases on Nov. 11, 1918, and no influenza deaths. The Chronicle on Nov. 18, 1918, urged the end of the masking order with an editorial headlined, “The Epidemic has Passed —And the Public Will Rejoice When Allowed Once More to Breathe Freely.” The city’s politicians eagerly declared victory, as the city reopened with packed theaters and bars.

Meanwhile, health officials eagerly addressed the influenza in the past tense. In what may be the pandemic’s “Mission Accomplished” moment, Red Cross President John Britton gathered volunteer workers to a packed luncheon hours after the order was lifted, declaring, “It is a great privilege to meet this indomitable band of workers today, and to see each of you exposing your complexion unmasked.”

It’s clear now that dropping the public’s guard was very premature. By early January, hospitals were full again with more than 25 influenza deaths per day, and on Jan. 11, 1919, the Board of Supervisors voted 15-1 to revive the citywide mask order.

“Supervisor Joseph Mulvihill, himself ill with influenza, sent word to the Board to have the minutes of the meeting record him as in favor of passing the ordinance to print,” The Chronicle reported.

Except this time, the we’re-all-in-this-together spirit in the city was gone. Citizens at the supervisors meeting filled the public comment with wild claims, including one man who touted miracle food from Russia that would cure the flu.

“May Dillonbeck told the Mayor and Supervisors that the situation would cure itself if the municipal authorities cleaned up the city, the water supply and the sidewalks,” The Chronicle reported. “One man, past 80, asserted he would not wear the mask and defied the authorities to arrest him. The Mayor invited him to sit upon the platform and the invitation was accepted.”

City leaders took little responsibility for their error. Mayor Rolph blamed outsiders for the resurgence of the flu, claiming that “… after San Francisco had successfully stamped it out the infection was brought to us once more by persons coming here from other cities.”

The politicians during the second wave had less success stopping large crowds from gathering; social distancing is now accepted as a better flu-prevention tactic than masks, especially the thin gauze masks of 1919. Under pressure from business leaders and worn-out citizens, the city did not recommend the shutdown of theaters, churches and schools. A vocal “Anti-Mask League” formed, gathering crowds so big that they moved meetings to a skating rink.

As of Nov. 23, 1918, two days after the city declared victory over the Spanish influenza, 1,857 deaths were reported in San Francisco, a city of about 500,000. By Feb. 28, 1919, when the ambush second burst of flu cases had mostly waned, that number had climbed to 3,213, with flu deaths still being counted.

(The Spanish flu killed a reported 500,000 Americans between 1918 and 1920, and more than 50 million worldwide.)

A century later, every word declaring an early 1918 victory is a blaring warning siren for the future, and anyone eager to declare a premature end to the fight of our lives.

“When the many chaptered epic of San Francisco’s share in the world war shall be written,” The Chronicle reported on Nov. 22, 1918, “one of the most thrilling episodes will be the story of how gallantly the city of St. Francis behaved when the black wings of this war-bred pestilence hovered over the city with its menace of death, sorrow and destitution.”

The city of St. Francis indeed behaved gallantly, for the first couple of months. And then its leaders let their guard down, and history tells a more tragic story.

Peter Hartlaub is The San Francisco Chronicle’s pop culture critic. Email: phartlaub@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @PeterHartlaub

Health San Francisco’s 1918 Spanish flu debacle: A crucial lesson for the coronavirus era - San Francisco Chronicle

0 Comments: