Media playback is unsupported on your device

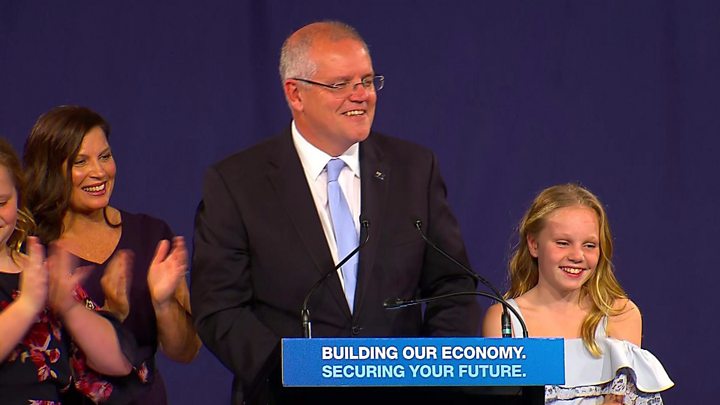

Australia’s ruling coalition was widely expected to be defeated in Saturday’s election after long trailing in opinion polls. But somehow, after just nine months as prime minister, Scott Morrison hailed a “miracle” victory.

In doing so, he defied a perception in Australian politics that leadership turmoil can only spell electoral doom.

Since the brutal ouster of Malcolm Turnbull last August, Mr Morrison has set about a disciplined strategy.

Some colleagues were considered toxic to the campaign trail, so Mr Morrison made this election about him, and his ability to be the trustworthy, daggy-dad Australia needed.

In the end it was very close but the voters decided, on balance, that Mr Morrison deserved the “fair go” he craved.

Here are three key ways he achieved it.

1. Remaking brand ‘ScoMo’

Before entering parliament, Scott Morrison was a marketing man who approved Tourism Australia’s infamous “So where the bloody hell are you?” campaign.

In politics he rose as a tough immigration minister, proud of his record in preventing boats of asylum seekers from reaching Australia, arguing it prevented drownings.

But when he became prime minister, he knew he had to change tack.

A social conservative and devout Christian, Mr Morrison pitched himself to voters as an everyday family man the country could trust.

He embraced the nickname “ScoMo” and slapped on a baseball cap at any opportunity, providing the internet with easily made fun.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Mr Morrison speaks often of his affection for the “Sharkies” – Cronulla’s rugby league team

He also made folksy pitches such as “a fair go for those who have a go” and often introduced people with the words “how good is”. After his victory on Saturday, the mantra was “How good is Australia!”

His efforts to project authenticity had sometimes appeared awkward, such as in a social media video where he sat, manspreading on his desk, deriding the “Canberra bubble” around him.

But though it drew ridicule, the strategy probably worked with many voters, according to Dr Andrew Hughes, a political marketing expert from Australian National University. “He was able to successfully appeal to the middle family segment in marginal seats with a more wholesome ‘dad’ brand image.”

2. Neutralising the ‘chaos’ factor

According to opinion polls, the toppling of Mr Turnbull caused an immediate drop in support for the Liberal-National government. But in the months since, polling showed the gap closing.

The same canvassing also showed that Mr Morrison was consistently favoured over Labor’s Bill Shorten as preferred prime minister.

That perception became central to Mr Morrison’s strategy to divert attention from the government’s recent bitter divisions over issues such as climate change and energy policy.

While Mr Shorten talked up his team approach, the prime minister painted the election as a choice between himself and the opposition leader.

He also sharpened his attacks. A telling moment took place in the final leaders’ debate when the men were told to ask each other two questions. Mr Shorten used both to promote Labor policies; Mr Morrison used his to criticise Labor policies.

Mr Morrison’s individual performance in the campaign was a success despite a lack of policies, says Prof Anne Tiernan of Griffith University. “The range of [government] talking points has been so limited by virtue of the many of the legacies that brought to him to the prime ministership.”

3. Making economic issues trump climate

Mr Morrison instead pushed the economy – traditionally his party’s perceived strength – to the centre of his campaign. He promised that his government would deliver better times ahead, while arguing that Labor would make people less prosperous.

Mr Shorten bet big on public sentiment to tackle climate change, and a wide-ranging reform agenda. But his message failed to cut through, particularly in Queensland, a large state with many conservative voters and disparate concerns.

Image copyright

EPA

Australians’ views greatly differ on a controversial coal mine planned for Queensland

Mr Morrison won numerous seats in Queensland after campaigning heavily there with a focus on job creation. Notably, he recorded big victories in electorates near a proposed coal mine which is to be built by Indian company Adani.

The mine in Carmichael has been hugely divisive in Australia. It has drawn fierce opposition from environmental activists, but many locals want it because it will guarantee jobs. The government supports the mine, whereas Labor has given mixed signals.

The state was crucial to his victory, and Mr Morrison singled it out for thanks in his victory speech: “How good is Queensland?”

What happens next?

Having won the improbable election, Mr Morrison will now wield significant power within his government.

But he faces key challenges to define the modern identity of his party in an era when its moderates and conservatives are in open conflict.

In the immediate term, Mr Morrison is expected to reconvene parliament so he can pass promised tax cuts. He has articulated some other priorities, but a broader agenda is yet to be defined.

The government is likely to face continued scrutiny on several issues, including efforts to tackle climate change, formally recognising indigenous Australians and female representation in parliament.

One government senator, Arthur Sinodinos, has already advised Mr Morrison to keep an open mind.

“One of the things, I think, he’ll have to do is take some of the elements of the Labor campaign and look at them and say: ‘Well, where were the issues that motivated some people to vote Labor, and what can I do to and ameliorate – assuage those concerns?’,” Mr Sinodinos told ABC on Saturday.

How Australia"s PM forged a "miracle" win

0 Comments: